Woodpeckers are a well known bird in the UK, up there with the Robin. However, despite all the woods and forests, Britain isn't that great for them. The UK has three resident types, the Great Spotted, Green and Lesser Spotted. A forth type known as the Wryneck which once bred sporadically in southern England is now only a very scarce migrant.

Great Spotted Woodpecker

The Great Spotted Woodpecker is a much loved bird for many people with feeders in their garden as they increasingly raid people's peanuts and suet, which is thought to be one of the reasons of their rapid increase since the 1970s and increased winter survival rates. Another being the Dutch Elm Disease, providing a huge increase in dead wood which provided a lot more wood-boring insects. There are thought to be 130,000 pairs in the UK at present, which is double the number in the 1970's. The decline in British ancient woodland is no problem for the Great Spot, as it becomes increasingly more reliant on garden feeders and spends more time in urban areas.

The Great Spotted Woodpecker's favourite food source is beetle larvae dug out from trees but they eat a wide range of other food including adult beetles, spiders, crustaceans, molluscs, flies and even carrion. It's also common for Great spots to raid bird nests and eat eggs or chicks and will repeatedly return to the same nest until it's empty. During the winter fat rich seeds, nuts, berries and sap provide a third of it's energy requirements, which is why garden feeders are increasingly being visited by Great Spotted Woodpeckers.

Great spotted woodpeckers are strongly territorial, typically occupying areas of about 12 acres all year-round, which are defended primarily by the male. This behaviour attracts females from December when courting begins. Pairs are monogamous during the breeding period, but it's common to find a new partner before the next season. Around mid-April as breeding season begins the pair begin excavating a new hole, never a reused one! Also at this point the classic drumming is at it's best, as territories are marked. Typical clutch size is between 4 and 6 eggs, with the incubation period being between 10 - 16 days, in which both male and female contribute.

A good sign the eggs have hatched is when your garden's pair of Great Spotted Woodpeckers suddenly start visiting multiple times an hour, filling their beaks with as much food as possible before flying off towards the nest...it's a notable increase in tempo!

The young fledge 20 to 23 days after hatching. Both parents continue feeding the brood for about ten days before the fledglings rapidly find their independence.

Fledglings can be identified by the red cap on top of the head, the males have a red square on the rear of the head and the females have no red at all on the head.

Green Woodpecker

The largest Woodpecker in the UK, the Green Woodpecker's population consists of just 46,000 pairs, which compared to the Great Spotted's 130,000 pairs, it's not surprising they're much harder to find. Thankfully though, the population more than doubled in the period from 1984 to 2004 and in 2015 were moved from the amber list to green. Green Woodpecker's eat Ants so don't compete with the dominating Great Spots on feeders or for wood-boring insects, but their dependence on ants makes them the most vulnerable species in cold weather and their rise in the last twenty years could only be helped by the milder winters.

Despite it's very striking green white and red plumage, the Green Woodpecker is a shy bird, that will hide behind trees or completely flee the area on sighting any threats.

They are most likely to be found in parks, golf courses, orchards or lawns, but due to the time spent low in the grass looking for ants, you're more likely to hear the Green Woodpecker's very loud 'yaffle' call than see them.

The tongue of the Green Woodpecker is so long it's curled around inside its skull and has sticky barbs at the end used for extracting ants.

Although green woodpeckers can pair for life, they are antisocial outside of the breeding season and preper to live alone. A breeding pair may continue to live near each other but they won’t re-establish their pair bond until courtship begins in March.

Like Great Spotteds, Green Woodpeckers nest in new self made cavities in trees and will not re-use any. They have one brood per year with a clutch of 4-6 eggs that are incubated between 19-20 days and fledging after 21-24 days.

The male can be identified by the red moustache stripe where as the females is solid black. Juveniles have a completely different appearance which are spotty and streaked all over. This is lost during the first moult which takes place between August and November.

Lesser Spotted Woodpecker

With the successful expanding population of the other two species of Woodpecker, the Lesser Spotted is looking to be more like a tragedy. Since 1970 the population has decreased by 83% and there are now thought to be fewer than 2000 breeding pairs left in the UK and still rapidly declining making them endangered and on the red status list. It's difficult to be certain why they're declining so quickly, but it's thought one of the reasons being the rapidly increasing abundance of Great Spotted Woodpecker which dominate over the much smaller, Lesser Spotted Woodpecker. Great Spotted's will regularly raid Lesser Spotted's nests, destroying the nest cavity in the process.

Another big reason for the decline is the loss of ancient woodland in the UK which is the Lesser Spots' natural nesting habitat. 6000 years ago Britain was over 90% woodlands and by 1900 just 5% due to timber production and land taken for farming. Tree planting however is increasing our woodlands and have increased from 5% to 10% in the last 100 years but ancient woodland has deteriorated from 5% to just 2%. The Lesser Spotted Woodpecker is dependant on rotting or dead trees in ancient woodland to feed on the wood-boring larvae inside and sadly this precious wood is being removed to improve the health and look of a wood.

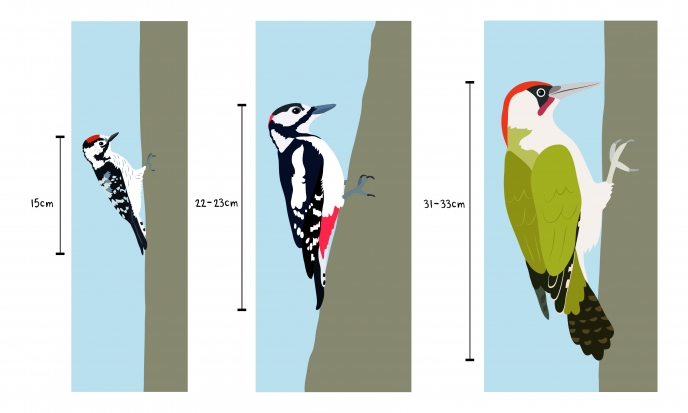

Dead standing trees, rotting wood on the ground and near a wetland or water source are characteristics of a good Lesser Spot habitat and can mostly be found on the edges of woodlands. Finding them is difficult, as they are much smaller than the other two species of Woodpecker, around the same size of a Sparrow as can be seen in this great diagram:

|

|

Left: Lesser Spotted; Center: Great Spotted; Right: Green Woodpecker | Image: Corinne Welch/Wildlife Trust |

Their size is one of the main reasons they're so hard to find, let alone count the population and maybe numbers are higher than predicted. They're also very quiet most of the year and spend their days at the tops of big oak trees foraging.

In February they begin drumming as they start to defend territories ready for the upcoming breeding season. During this year's breeding season I struck gold when I was sat on Dartmoor in the middle of 6 Lesser Spots all fighting over a corner of a woodland, which they finally resolved 3 days later.

They usually always excavate a nest in a limb of a tree, usually in dead wood or softer wood such as alder, willow, birch, poplar, sycamore and beech.

The nest will usually be high up in the tree up to around 40 feet. Whilst the nest entrance hole is only about 1-2 inches wide, the nest itself has a pair shape appearance that extends down around 12 inches below the entrance hole. 4 - 6 eggs are laid around late May, both birds taking turns to incubate them, which hatch after 14-15 days, which then fledge between 19 - 22 days. The fledglings are mainly fed with surface-living insects, such as aphids, larval insects and flies.

Wryneck

So I've written about two thriving Woodpecker species in the UK, a rapidly declining one and now for a type now extinct from Britain. Once a common breeding bird in Britain, the Wryneck began to decline at the start of the 19th Century, only common in the south east by 1900 and by 1950 it was only common in Kent. the Wryneck is now extinct as a breeding bird in Britain. The only way of seeing these birds in the UK now, is catching the odd few passing through at the end of breeding season in August/September as they migrate back to Africa from Scandinavia. As was the case this year, during strong easterly winds more Wrynecks than usual will be blown towards the UK.

Just like Green Woodpeckers, Wrynecks need tall trees for nesting and protection but feed mainly on ants on bare ground.

The main reason for the Wryneck’s decline in Britain seems to be the intensification of agriculture. 500 years ago, farming was on a much lower scale for local consumption. Today most farming is carried out at an industrial level for profit, which land is managed intensively, increasing productivity of the land. Hedgerows have been removed, woodlands cut down and pasture changed to crops to streamline production using machinery, fertilisers and pesticides. For the Wryneck in particular, the loss of wooded pasture and traditional orchards have probably been the most significant factors affecting its presence.

Compared to other woodpeckers the wryneck has a short beak which is not well-suited to digging so it's not able to make its own nest hole, preferring to breed in tree-holes created by other birds or even nest boxes.

Wrynecks usually commence their migration in May towards Scandinavia, with a few passing through the UK on the way. They return back to Africa late August / early September with numbers boosted with the added juveniles.

Nests they use will not be lined with materials and will be whatever well suited hole is available at the time, whether it be in a tree trunk, a crevice in a wall, a hole in a bank, a burrow or a nesting box.

A single clutch of between 7 to 10 eggs is laid with both birds in the pair involved in incubation which takes 12 days. Once hatched, both parents feed the chicks for about twenty days before they fledge.